E- ISSN: 2709-5533

Vol 4 / Jan - Jun [2023]

globalrheumpanlar.org

Columns

Lichen on a tombstone

Autor: Fernando Neubarth: Especialista em Clínica Médica e Reumatologia. Correo: neubarth@terra.com.br

DOI: https://doi.org/10.46856/grp.22.et145

Cite: Neubarth F. El liquen en la lápida. Global Rheumatology. Volumen 4 / Ene - Jun [2023]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.46856/grp.22.e145

Received date: 1/12/2022

Accepted date: 15/12/2022

Published Date: 18/01/2023

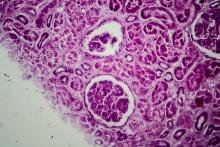

Psoriasis is probably as old as mankind. Despite its frequency, chronic nature, and visibility, it remains challenging to find an unequivocal description of it in ancient medical records. Different authors referred to psoriasis by various names, while at the same time, several different diseases were given the same name.

It was only at the end of the 18th century that psoriasis was first recognized as a distinct entity. However, until the 20th century, descriptions remained vague. Added to this is the somewhat late understanding of the rheumatic condition beyond the skin disease, psoriatic arthritis. Nowadays psoriasis is well-defined as a disease involving genetic, environmental, and immunological factors.

This history of misunderstanding and uncertainty is also responsible for the fear associated with a non-existent possibility of contagion and the unimaginable suffering of those with psoriasis, immeasurably greater due to the long elaboration of prejudice that still resonates today. This is mostly due to the diagnostic confusion with leprosy, the greatest example of stigma and social segregation associated with a disease in the history of civilization.

The misunderstanding is so great that, contrary to what is mostly assumed, leprosy is not a "biblical disease". None of its characteristic signs appear in the Old Testament. The "tsara'ath" of the Hebrew holy books meant moral degradation and was based on a confusing and varied series of skin and scalp alterations that could correspond today, more appropriately, to parasitosis, pyodermitis, vitiligo, pemphigus, and psoriasis itself. Its bearer was considered unclean by the priest and banned from social life, while clothes with "tsara'ath", probably just moldy, were burned and destroyed, and the remains and even the stones of the walls of the houses were taken to an "unclean place".

On the initiative of Ptolemy II, the Philadelphus, the Hebrew Torah, Neviim, and Ketuvim were translated into Greek and became the Bible. When the 70 or 72 Jewish scholars charged with the task came across the "tsara'ath," they found nothing better than "leprosy," a Greek word meaning scaling and exfoliation (from the same root as "book"), which possibly, in this Hellenistic phase, had a connotation of impurity or dishonor. They were certainly not referring to leprosy, since this was known to the Mediterranean peoples of the time under other names - "elephantiasis" among the Greeks.

An emblematic example is a scene from Ben Hur: A Tale of the Time of Christ, by the American general Lewis "Lew" Wallace (1827-1905), published in 1880 and brought to the movies in more than one version. In this passage, the mother and sister of the character Judah Ben Hur, confined among other banished "lepers", rush through the crowd eagerly awaiting the arrival of Jesus, the one who, everybody said, welcomed and cured the sick:

- “Closer, my child, let's draw closer. He can't hear us”, said the mother.

She stood up and staggered forward. Her repulsive hands were raised and she screamed with horrible shrillness. The people saw her, with her horrible face, and stood in astonishment, an effect by which extreme human misery, visible as in this case, is as potent as majesty in purple and gold. Tirzah, a little behind her, fell too weak and frightened to move on.

- The lepers, the lepers! - they shouted. Stone them! - God curses them! Kill them!

Nothing to justify it, but was leprosy really what Tirzah and her mother had?

John Updike (1932-2009), an American writer, novelist and literary critic, a psoriasis sufferer, described his condition in a literary text (From the Journal of a Lepper) and in a memoir (At War with my Skin): "Leprosy is not exactly what I have, but what was called leprosy in the Bible was probably this thing, which has a sinister Greek name that pains me to write. The form of the disease is as follows: patches, plaques, and avalanches of excess skin... They expand and migrate slowly through the body like lichen on a tombstone. I am silvery, flaky. Puddles of flakes form wherever I rest my flesh... My torture is superficial... We - the lepers - are lustful, though we are loath to love with a keen eye, though we hate to look at ourselves. The name of the disease, spiritually speaking, is humiliation."

From the early days until the 19th century, when it was advocated that psoriasis was the result of an internal metabolic disorder and arsenic its systemic treatment of choice, many therapies were proposed. Among the topical ones, are phototherapy and some very peculiar ones such as ichthyotherapy: the use of scale-removing fish. Much progress was made until the 21st century, when it was recognized as a disease of the autoimmune system, allowing the development and use of biological medicines and a better understanding of psychosocial factors involved in aggravation and also in therapeutic support. The good results, based on science, open the perspective of minimizing a long history of suffering and pain that is felt in the core and in the surface of the skin, mainly due to the prejudice that ignorance - always it - imposes.

P.S. In 2018, I was invited to write a chapter in the book " Psoriatic Arthritis", edited by my colleagues Rafael Alba Fériz, Roberto Muñoz Louis, Luis R. Espinoza y John D. Reveille and published in the Dominican Republic. I stopped at the history of the disease itself and passed on the invitation to a dermatologist colleague, Dr. Jaquelini Barboza da Silva, in a division of tasks and encouraging her to tell the story of the treatments. The text above is an excerpt, a part of my share of what resulted in this publication (Neubarth, F; Silva, JB. History and evolution of psoriatic arthritis. In: Fériz, RA; Louis, RM; Espinoza, LR; Reveille, JD. (Org.). Libro Texto Artritis Psoriasica. 1ed. Santo Domingo, Rep. Dominicana: Editora Corripio, 2019, v. 1, p. 3-20.)