At the end of the 20th century, Bernard Lown warned that, despite all the technological advances in the diagnosis and treatment of many and varied diseases, the patient had become even more neglected. Medical practice tied to a complex, entrepreneurial gear, especially in the North American model, attention not necessarily to the promotion of health and well-being. Doctors and, especially, patients pressured by the growing supply of exams, sometimes excessive and inadequate. Under pressure from the pharmaceutical industry, diagnostic equipment and resources, insurance and assistance plans, resulting in paradoxical insecurity, dubious "alternative" options, and unscrupulous "judicialization". Something had been lost.

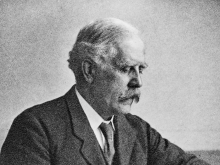

Bernard Lown was born in Utena, Lithuania, on June 7, 1921, and the family emigrated to the United States in 1935, threatened by Nazism. He graduated in Zoology at the University of Maine in 1942 and in Medicine at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore in 1945. After internships in Connecticut and New York City, he moved to Boston in 1950, and in the following decade he taught and led cardiovascular research at Peter Bent Brigham Hospital and Harvard Medical Scholl until, due to McCarthyism, he began to work in public health and at his own Institute.

In 1962, Lown developed, with the help of medical engineer Barouh Berkovits, a new method to correct dangerously abnormal heart rhythms. At the time, considered to be the cause of 40% of half a million fatal heart attacks per year, in the United States alone, fibrillations began to be treated by this new model of defibrillator, which used continuous electric current instead of alternating current, without harming the heart. There, intensive care units also appeared there and it is incalculable how many early deaths have since been avoided. Lown also encouraged the patient to "get out" of bed early after a heart attack, a practice that is now natural; and his name appropriately designates a scale that grades the severity of arrhythmias.

He founded SatelLife USA, a non-profit organization that even has a satellite to assist professional clinical training in Africa and Asia, and ProCor, a global web communication network that promotes assistance and education for developing countries.

Instigated by a lecture on medicine and nuclear war, in 1961 he founded Physicians for Social Responsibility. The following year he published a study speculating the public health consequences of a hypothetical nuclear attack in Boston, concluding that the attack on a city would deplete all medical resources in the country just to treat burn victims. He helped found the organization International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War, a partnership between American and Soviet doctors. The group totaled 135,000 members in 41 countries in 1985, the year it received the Nobel Peace Prize. Soviet participation, however, made conservative criticism undermine the movement, imputing to its leaders a naive bias and therefore the suspicion that would serve the "communist" propaganda. In a 2008 memoir, Prescription for Survival: A Doctor's Journey to End Nuclear Madness, Bernard Lown tells this story and warns: "It is a historic challenge to question whether we humans have a future on planet Earth".

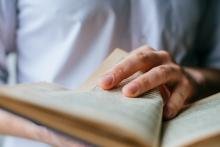

Before, in 1996 he published the book The Lost Art of Healing, a book to the rescue of humanism in medicine, enchanting and encouraging everyone who believes that a good doctor-patient relationship is not only the main instrument of practice but the pragmatic antidote for the many ailments that undermine confidence and the best outcomes.

He recalls Hippocrates, 2,500 years ago: “Wherever there is human love, there is also a love of art. Some patients, although aware of their dangerous situation, recover their health simply because of their satisfaction with the doctor ”. Bernard Lown follows the path of other thinkers in medical art. Like Paracelsus, in the 16th century, who included among the basic qualifications of the doctor “the intuition necessary for the understanding of the patient, his body and his illness ... He must have the feeling and the touch that enable him to enter into solidary communication with the spirit of the patient ”, and, in the same way as William Osler, who, in the last decades of the 19th and early 20th centuries, understood medicine not only as science, but as“ the art of medicine in the light of science ”and affirmed that “the good doctor treats the disease, the great doctor treats the patient who has a disease”.

In the midst of the pandemic, which subverts precepts and convictions and reaffirms values; Bernard Lown says goodbye. He died at his home in Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts, on February 16, 2021, at the age of 99. Innovative cardiologist physician, social activist, and nuclear antiwar, and, above all, a gigantic humanist. His legacy is guaranteed: "The doctor must rely on the art of human understanding to broaden the vision that science gives him". This statement is broad and serves the whole society.