At the beginning of the 18th century, Herman Boerhave, a Dutch physician, used his 10 beds at the Leiden hospital to teach. Students from all over Europe, Great Britain and the American colonies came there to receive his teachings at the bedside of the patients.

This was the beginning of clinical practice. Along with the Leiden school, Edinburgh and Paris were the most important in the western world, followed by Oxford and Cambridge. From this period stand out Monroprimus, Monrosecundus, Thomas Pervical and James Gregory.

Few 18th-century physicians excelled from Oxford and Cambridge. But in the second half of the century there was Willian Heberden, a Cambridge graduate. Cambridge students had a classical, nationalistic, and “armchair” mentality medical training, as they were lagging behind with the few advances in medicine of the time, such as physiology, pathology, semiology, hygiene, and therapeutics.

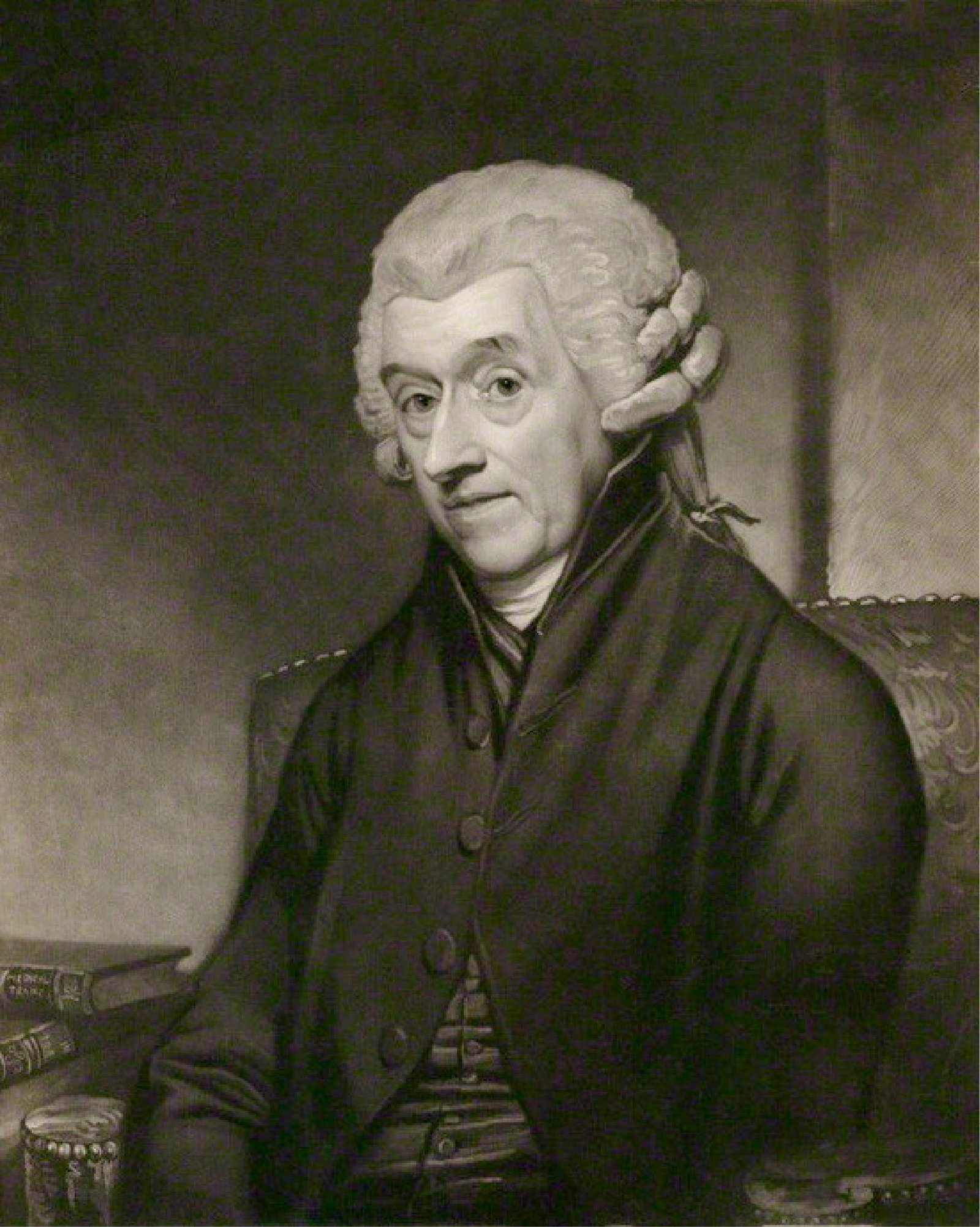

It is William Heberden whom we will talk about this time. We have already talked about Thomas Sydenham in the 17th century and now we move on to the 18th century to discover more about the beginnings of rheumatology.

Photo 1. William Heberden. Mezzotint by J Ward Sir W. Beechey

How would William Heberden introduce himself?

I was born in London in 1710. My early studies were at the parish grammar school of St Saviour in Southwark, an Elizabethan foundation providing free education. I attended St John’s College in Cambridge (1724), where I obtained my BA and at the age of 29, I was awarded my MD (1729).

I was in Cambridge for 10 years where I was practicing, learning, and teaching medicine. During that time, I was responsible for the annual course in medicine and therapeutics. After practicing there, I returned to London where I was admitted as a fellow of the Royal College of Physicians, in 1746; and then, in 1749, I was offered the prestigious Goulstonian lecture as well as being the Havernian orator in 1750. In addition, in 1763 I was one of the founders of the Medical Transaction of the Royal College, a forum whereby members could report their observations in patients in the form of clinical case presentations.

I enjoyed the classics and was known because during the courses I frequently quoted these authors in Latin, to illustrate the commentaries (Figure 1).

In the 1782 preface to the Commentaries on the History and Cure of Diseases, I wrote in Latin “Plutarch says that the life of a vestal virgin was divided into three parts, in the first of which she learned the duties of her profession, in the second she exercised them, and in the third, she taught them to others” and I added: “this is not a bad model for the life of a physician, and as I have passed through the first two, I am willing to spend the rest of my days in teaching” (1).

One of your many virtues was discipline…

Yes, indeed. I took notes of my patients and organized their histories in English or Latin. From this, in 1766, I proposed to the Medical College to periodically publish the contributions of each of its members under the title of Medical Records. Three volumes were published.

How was the process of description of nodules?

I am aware I am now best known for the description of the nodular swellings in osteoarthritis, the “Heberden’s nodes” which are talked about daily, especially by rheumatologists.

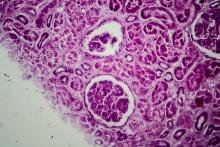

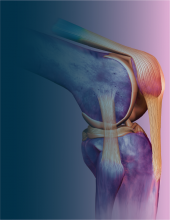

The classic description I gave was the Latin name digitorum nodi (Figure 2 and 3), which describes them as "hard nodules in the distal interphalangeal joint that are unrelated to gout and persist throughout the patient's life. I defined them as hard nodules, about the size of a pea, that can often be seen on top of the fingers, especially a short distance from the end and close to the joint. They have no relation to gout, may be seen in persons who have never suffered from it; and persist throughout life, being scarcely ever accompanied with pain, or ready to become sores, they are rather unsightly than inconvenient, though they must be some small obstacle to the free use of the fingers."

Photos 2 and 3. Description and photo in Latin of the Heberden’s nodes

But it did not stop there…Your observations reached cardiology as well

Yes, I described angina pectoris. I first presented it in the London Medical Act where I spoke of a disease known as angina pectoris, a communication that aroused a lot of excitement and that attracted the attention of physicians. Shortly thereafter I published further observations on this subject, with a case study and autopsy findings.

Do you believe you reached milestones in medicine with your observations and writings?

The book “Commentaries on the history and cure of diseases”, edited by my son William (Willian Heberden, the Younger), is one of the most widely read classic medical books in the world. It describes the digitorum nodi, which, as I said, today are known by my name.

But I believe I should not only be remembered for the nodules, I also described differences with gout, of which I described some characteristics. "It should be known that there are cases in which the criteria of both are so mixed together, that it is not easy to determine whether the pains are gout or rheumatism”.

I described what is today known as hypersensitive vasculitis. “Some children, with no health disturbances at the time, nor before, nor after, have got purple spots all over the body, just like those seen in purple fever. In some places they were not wider than a seed, in others they were as wide as the palm of the hand, within a few days they disappeared without medication. It was remarkable that in one of these spots, the slightest pressure was enough to extravasate blood thus making it look like a hematoma. Sometimes they had stomachache with vomiting, and at that time some streaks of blood were perceptible in the stool and urine was tinged with blood. When the pain attacked the leg, they could not walk” (2). I also wrote something about lumbagos, undefined rheumatisms (fibromyalgia?) and convincing descriptions of tuberculous arthritis of the hip and acute rheumatism (rheumatic fever).

I was a faithful follower of the Hippocratic concepts, so I wrote and compiled all my observations in Commentaries on the History and Cure of Diseases, written in Latin and translated by my son into English.

But your research had a far wider scope…

In 1767 I described night blindness and the clinical aspects of chickenpox, and also began the fight against the pharmacopeia of magic remedies, the use of some folk remedies such as Fowler´s solution and fruits loomed on the horizon.

Thus, English medicine in the 18th century received two related orientations: semiographic and nosographic empiricism on my part, which was the heritage of Sydenham, and anatomoclinical research.

I also had great interest in preventive medicine and an example of this is illustrated in my “Remarks on the pump-water of London”, where I warned about the dangers of contamination, recommending either distilling or filtering water before it could be consumed. Also, as a curious fact, there is a plant with my name (Hebernia) (2).

What other things did you do?

I recognized chickenpox and smallpox as two distinct entities, I also engaged in preventive medicine in which there was the need of filtering water before consumption.

I collaborated with Benjamin Franklin in preparing a pamphlet advising parents how to vaccinate their children against smallpox for use of the English colonies. In view of the great culture for that time, Samuel Johnson, called me “the last of the Romans” for what he calls my extraordinary culture.

I understood medicine from a holistic perspective, that is also important. When I knew that a symptom did not have definite treatment, then I would look for the patient to be in a quiet environment, with fresh air, baths, and at some points I would recommend a change of routine.

My distinctions and scientific societies:

Fellow of the Royal Society

Croonian Lecture (1760)

Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians (1746)

Goulstonian Lecture (1749)

Harveian Oration (1750)

Your greatest legacy?

I am regarded as both the father of clinical observation of the 18th century and also the founder of rheumatology. Someone said, "His distinguished knowledge, gentleness of manner and active benevolence, raised him to a rare high place in public esteem".

In 1936 half a dozen physicians working at the British Red Cross Clinic of Rheumatism founded the Heberden Society for the advancement of the study of rheumatology, which after 46 years was merged with honors into the British Rheumatology Society.

Heberden died at the age of 91. His legacy includes the essential ingredients of medicine: the art of observation, critical assessments of observations and, importantly, compassion for his patients.

William Heberden is justly regarded as one of the most illustrious physicians of the 18th century (3).

References:

- Talha Khan Burki. William Heberden.The Lancet ( 2, 4, E20, April 2020). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2665-9913(20)30062-X

- Buchanan, W.W., Kean, W.F. William Heberden the elder (1710–1801): the complete physician and sometime rheumatologist. Clin Rheumatol 6, 251–263 (1987). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02201032

- T. Y. Lian, K. K. T. Lim, The legacy of William Heberden the Elder (1710–1801), Rheumatology, Volume 43, Issue 5, May 2004, Pages 664–665, https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keg00

Recommended readings

- Lain Entralgo. P. Historia universal de la medicina. Tomo V, páginas 65,123,145,268. Sar Vat. Editors, S.A-Reimpresion 1976.

- Heberden W. Some account of a disorder of the breast Medical Transactions. The Royal college of Physicians of London 1772;2:59-67.

- Bendiner E: William Heberden: father of observations. Hosp Pract (off Ed) 1991;26:103-106,109,113-6.

- Fernández-Vázquez JM, Ayala-Gamboa U, Camacho-Galindo J. William Heberden (1710-1801). Acta Ortopédica Mexicana 2011; 25(3):195-6. Available at: https://www.medigraphic.com/pdfs/ortope/or-2011/or113l.pdf

- Thierer J. William Heberden, y su inolvidable descripción de la angina de pecho. Sociedad Argentina de Cardiología. 2018. Available at: https://www.sac.org.ar/historia-de-la-cardiologia/william-heberden-y-su-inolvidable-descripcion-de-la-angina-de-pecho/

Figures

Photo 1

William Heberden. Mezzotint by J Ward Sir W. Beechey: Available at Wikimedia

Photo 2. Original description in Latin of the Heberden’s nodes (Wikimedia)

Available at:

Photo 3

Figure 3.

Heberden’s nodes. Retrieved from: Reumati.co American College of Rheumatology ACR https://sites.google.com/reumati.co/reumatologia/osteoartritis